A circuit-like notation for lambda calculus

Lately, I’ve been playing around with inventing a visual writing system for lambda calculus.

Lambda calculus (λ-calculus) is a sort of proto-functional-programming, originally invented by Alonzo Church while he was trying to solve the same problem that led Turing to invent Turing machines. It’s another way of reasoning about computation.

Python’s lambda is an idea that was borrowed from λ-calculus. In Python, you can use a lambda expression like the following in order to define a function that returns the square of a number:

square = lambda x: x * x

In λ-calculus, the idea is the same: we create a function by using λ to specify which arguments a function takes in, then we give an expression for the function’s return value. Pure lambda calculus doesn’t include operators of any sort – just functions being applied to other functions – so if we try to write a square function, we have to suppose that multiply is a function of two variables that has already been defined:

square = λx. multiply x x

The square function, once defined, can be applied to arguments and evaluated into something simpler.

square 4 = (λx. multiply x x) 4

= multiply 4 4

= 16

One of the cool things about lambda calculus is that we can represent most common programming abstractions using λ-calculus, even though it’s nothing but functions: numbers, arithmetic, booleans, lists, if statements, loops, recursion… the list goes on. Before I introduce the visual writing system I’ve been using, let’s take a detour and discuss how we can represent numbers and arithmetic using lambda calculus.

Church numerals, in lambda calculus

Alonzo Church figured out how to represent numbers as lambda functions; these numbers are referred to as Church numerals.

We can represent any nonnegative integer as long as we have two things: (1) a value for zero, and (2) a successor function, which returns n + 1 for any number n. To represent numbers as functions, then, we require that z (zero) and s (successor) be passed in as arguments, and go from there. Each number is actually secretly a function of those two inputs.

zero = λs. λz. z

one = λs. λz. s z

two = λs. λz. s (s z)

three = λs. λz. s (s (s z))

The actual details of how to implement zero and successor should be implemented as are left as someone else’s problem — we can survive without them. All we care about is that our numbers do the right thing, given whatever zero and successor someone may provide.

What about addition? Addition is a function that takes in two numbers (let’s call them x and y), and produces a number representing their sum. To sum them together, we’ll want to produce a number that applies s, the successor function, a total of x + y times. For example, we could first apply it y times to the zero, then apply it x more times to that result.

plus = λx. λy. (λs. λz. x s (y s z))

Let’s try proving that one plus one equals two. In λ-calculus, this proof looks like the following:

one = λs. λz. s z

two = λs. λz. s (s z)

plus = λx. λy. (λs. λz. x s (y s z))

plus one one = (λx. λy. (λs. λz. x s (y s z))) one one

= λs. λz. one s (one s z)

= λs. λz. (λs. λz. s z) s (one s z)

= λs. λz. s (one s z)

= λs. λz. s ((λs. λz. s z) s z)

= λs. λz. s (s z)

= two

(Long, but at least conciser than Bertrand Russell’s.)

Lambda circuitry

There are a lot of lambdas, parentheses, and arguments being pushed around in that proof. Mentally matching up parentheses is annoying. Scope is especially annoying: which s am I looking at again in λs. λz. (λs. λz. s z) s (one s z), the inner one or the outer one?

A linear string of lambdas and parentheses is an ineffective way to provide intuition for the computations that are taking place. This problem isn’t unique to lambda calculus, either; consider trying to represent a binary tree using a linear string:

Node(2, Node(7, Leaf(2), Node(6, Leaf(5), Leaf(11))), Node(5, None, Node(9, Leaf(4), None)))

Unambiguous, but not very intuitive. Contrast that representation with the diagram we use when we’re trying to explain that same binary tree at a chalkboard, a more visual notation:

Image from Wikipedia.

I remember programming constructs better when I can reason about them visually like this: when I imagine cutting an array in half for binary search, when I imagine pointers in a linked list being shuffled around to insert a new element, and when I imagine traversing up and down the branches of a binary tree.

Why can’t lambda calculus get some visual intuitions, in the same way? Lambda calculus is a dance of variables flowing through and being manipulated by functions, and I want a writing system for lambda calculus that will visually display this dance. It shouldn’t look like strings of parentheses and symbols: it should create visual intuition.

After some trial and error, here is the system I came up with. I aimed for something that would resemble circuitry.

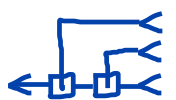

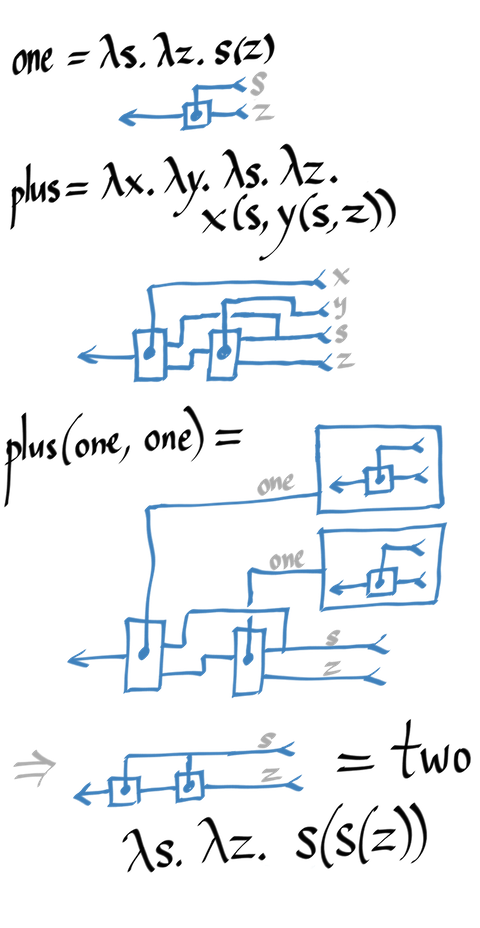

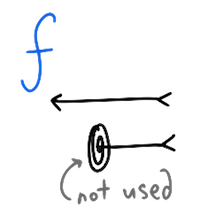

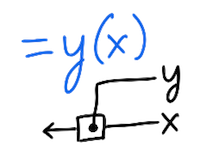

Values flow along wires, where they may be passed in as arguments to functions or applied as functions themselves. Some are inputs, some are outputs.

Functions are represented as boxes which are applied to their inputs on one side and produce a single output on the other. The notation must indicate which function is applied; this may either be drawn within the box itself, or wired in to the middle of the box from some other value.

Arguments are represented as inputs, coming in from the right side of the diagram; these arguments might pass through functions, or they might be functions-to-apply themselves. If an argument has not been passed in yet, it’s an empty arrow beginning a wire; if an argument has been passed in, its value is attached to the wire. Arguments are always passed in from top to bottom, in order.

As an example, here’s a function which takes in two functions, f and g, then a value x, and returns f (g x):

As another example, here’s the M combinator M = λx. x x (the “mockingbird” in To Mock a Mockingbird):

Church numerals, in lambda circuitry

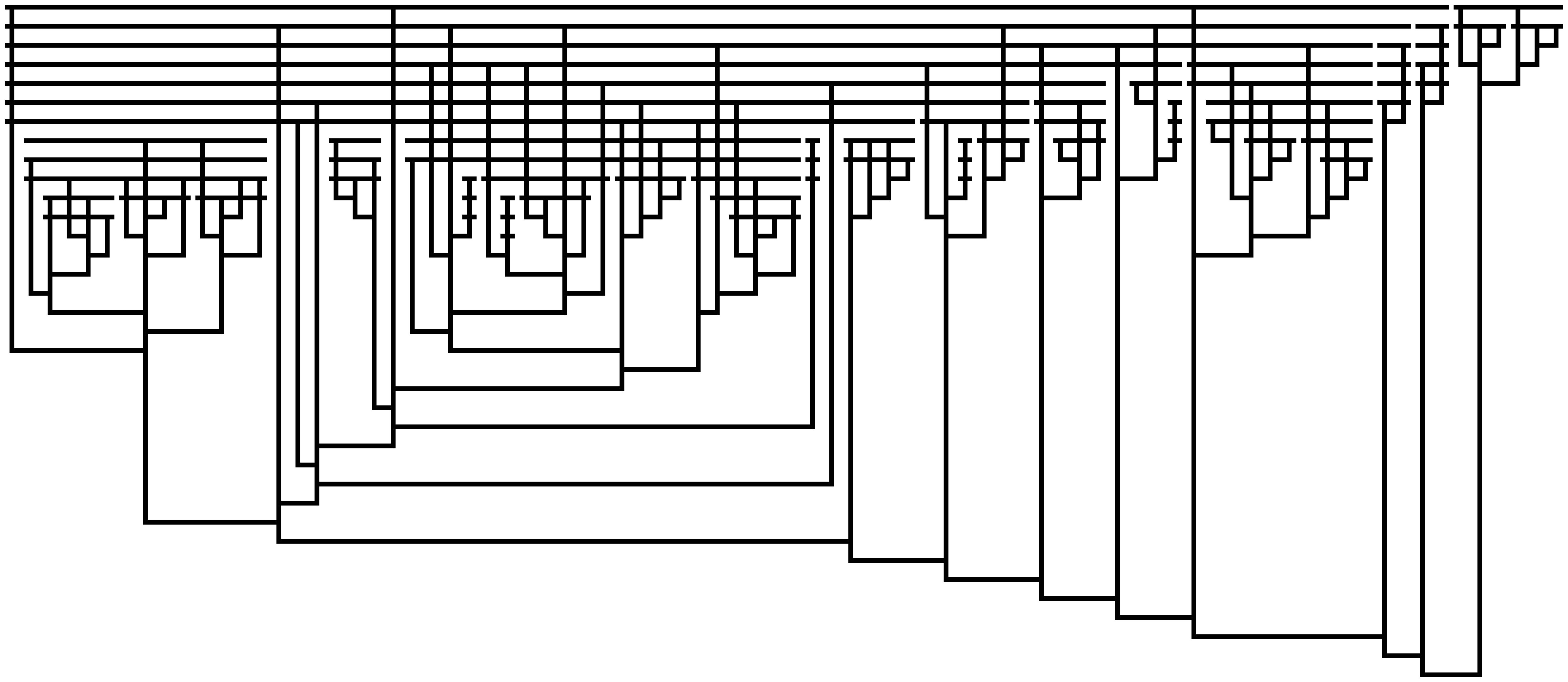

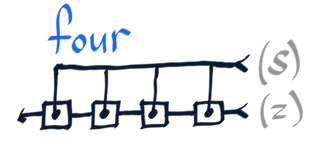

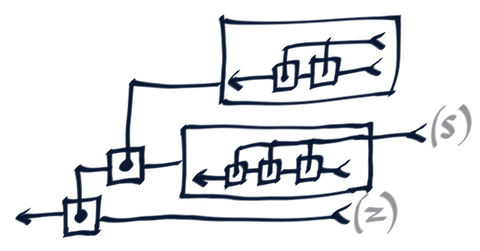

Here’s the Church numeral four = λs. λz. s (s (s (s z))), drawn out in lambda circuitry:

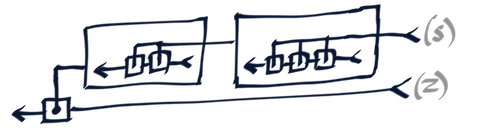

Let’s take that proof from earlier that one plus one is two. What does it look like to draw that proof in lambda circuitry, instead?

∎

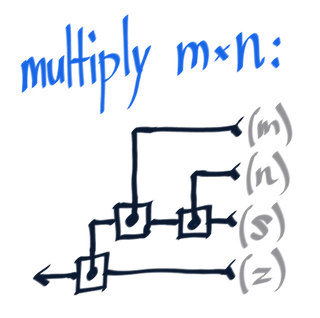

We could also consider multiplication. A multiply function would take in two numbers, m and n, and computes a new number which is their product. In lambda calculus, we’d write:

multiply = λm. λn. λs. λz. m (n s) z

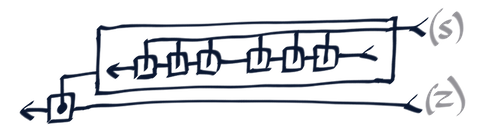

In the notation of lambda circuitry, this looks like this:

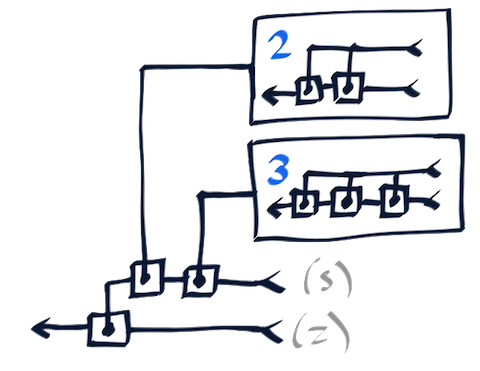

Using this function, we can check that multiply 2 3 evaluates to 6:

∎

Sidenote: De Bruijn indices

One of the nice things about lambda circuitry is that it completely removes the need for variable names.

There’s another notation for lambda calculus that does this too: De Bruijn indices. A lambda expression written with De Bruijn indices indicates which variables are used where with a positive integer; the smaller the integer, the more recently the argument it refers to was passed in.

For example, the identity function λx. x may be written with De Bruijn indices like so:

identity = λ 1

The Church numeral for two, λs. λz. s (s z), may be written like so:

two = λ λ 2 (2 1)

The addition function, λx. λy. (λs. λz. x s (y s z)), may be written like so:

plus = λ λ (λ λ 4 2 (3 2 1))

An evaluation of plus one one looks like this:

plus one one = (λ λ (λ λ 4 2 (3 2 1))) (λ λ 2 1) (λ λ 2 1)

= (λ (λ λ (λ λ 2 1) 2 (3 2 1))) (λ λ 2 1)

= λ λ (λ λ 2 1) 2 ((λ λ 2 1) 2 1)

= λ λ (λ λ 2 1) 2 (2 1)

= λ λ 2 (2 1)

One of the tricky things about writing a lambda calculus interpreter is getting the renaming rules right; De Bruijn indices are convenient because they remove the need for this. Lambda circuitry is similar in spirit to De Bruijn indices in that it doesn’t require variable names at all, but instead indicates which variables are passed where by connecting values directly to an arrow indicating when they were passed in.

Argument-switching function, in lambda circuitry

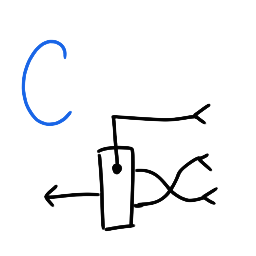

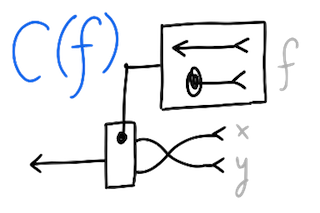

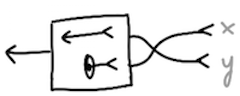

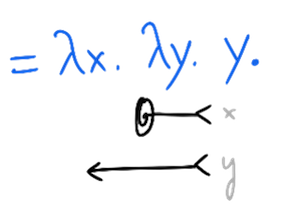

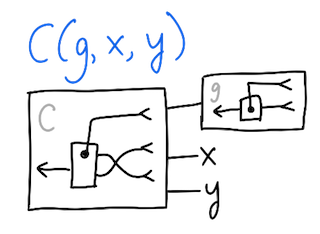

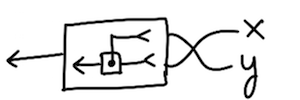

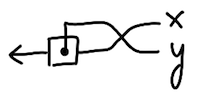

I’ll provide more examples just to further demonstrate how the notation works in different situations. Let’s consider the “argument-switching” function C, where C f x y returns f y x. (This is actually the C combinator.)

C = λf. λx. λy. f y x

Suppose we try applying this to a silly function f where f x y discards y and just returns x. Then, C f should switch around f‘s arguments and create a function which returns y instead. Let’s check:

f = λx. λy. x

C f = λf. λx. λy. (f y x) f

= λx. λy. f y x

= λx. λy. (λx. λy. x) y x

= λx. λy. y

∎

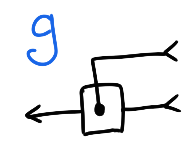

We could also try a function g where g x y returns x y. Then C g x y should return y x. Let’s check:

g = λx. λy. x y

C g x y = λf. λx. λy. (f y x) g x y

= g y x

= (λx. λy. x y) y x

= y x

∎

Exercise: Show that applying C twice reverses it. That is, show that C (C f) returns f, for any f.

(Note that C f is a function which takes in two arguments, x and y, and returns f y x. Applying C only to f like this is partial application.)

Prior work

There are some other systems that give visual intuition to lambda calculus.

To Dissect a Mockingbird describes a notation that is actually very similar to the one I’ve described, and demonstrates it on various problems from To Mock a Mockingbird. I like the way this looks, especially how every function is enclosed by two halves of a circle which make it obvious how that function might be applied. My notation doesn’t have this feature, but requires drawing fewer enclosing boxes as a result.

Visual Lambda (code, basics, paper) represents lambda expressions as colored bubbles, and provides an interface for manipulating them.

Alligator Eggs is a description of a puzzle game based on lambda calculus, which also happens to provide a visual way of working with and evaluating lambda expressions.

These last two don’t happen to satisfy the aesthetic that I personally was aiming for: they use color to represent variable names, whereas I wanted something that would be closer in spirit to De Bruijn indices, providing computational meaning by the careful placement of symbols or wires – but they are nifty nonetheless.

Further reading

An explanation of some of the nittier, grittier details of lambda calculus can be found at Wikipedia: Lambda calculus as well as in the textbook Types and Programming Languages.

To Mock a Mockingbird is a great puzzle book, and an introduction to combinator calculus; I had a lot of fun reading it and writing out some of the proofs for answers to some of the problems in lambda circuitry notation.

Updates

2020-08-18

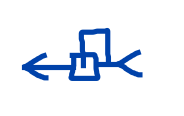

Since this piece was written, I have discovered another notation by John Tromp which I consider to be the most breathtakingly beautiful:

Here used by Paul Crowley to describe Graham’s number: